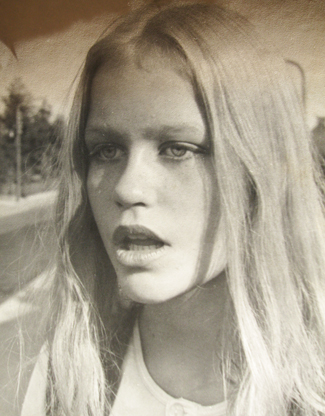

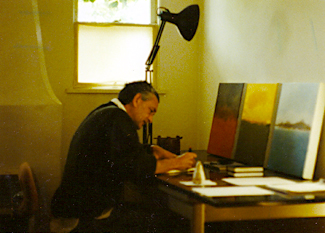

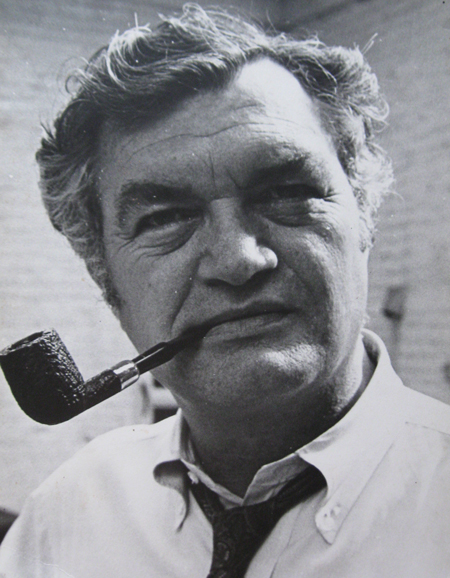

Seymour Boardman, painter, with the Artist, NYC, 1999.

|

One doesn't really know where to begin this stuff: So I'll just dive in. As the story goes, I was conceived in my uncle's sculpture studio. My uncle was a very talented sculptor when he was young, but he gave it up. Years later, after it was clear that I was an artist, we talked about it, and he told me he never felt he was a real artist. He said he lacked the creative part. I was eight years old when I made my first work of art. On a visit to the beach, I took a long walk along the shore and a piece of driftwood caught my eye: It looked exactly like the body of a duck. I spent the next two hours, looking for its head. I found it. No carving was done to either of the two pieces. My Dad helped me glue the head onto the body, and from then on, he always kept it on the wall above his desk, at home. |

|

About a year later, my first love affair with Beauty began: Mineral crystals. I had been introduced to rock collecting at summer camp, and what I liked the most were crystals. At home, I would spend hours looking into tiny pockets of crystals, with a 5x magnifying glass, in search of the perfect cube, octahedron, quartz crystal, garnet dodecahedron: Anything formally perfect. I didn't know it at the time, but I was attracted to ideal form. Years later, as a mature painter, I realized that I got my sense of natural color not from flowers, but from mineral crystals. I still collect perfect crystals, and never tire of their beauty. |

|

At age 10 I started taking classical guitar lessons. Within a matter of months, I had discovered Beauty again, this time in contrapuntal music. I began listening to records of Segovia from whom I first really experienced Bach. For my 11th birthday, my grandfather took me to hear Segovia live, at Town Hall. I particularly remember the old master, alone on the stage, stopping in the middle of a piece, to tune a string: I think I learned from that that the Artist is supposed to be an uncompromising perfectionist. Later I found out that Segovia practiced 8 hours a day. One day, my Dad came home with a record he had bought for me: Carlos Montoya, "Flamenco." I still have it. He put it on and the minute I heard the first tune, "Malaguena," that was it for me. I switched from classical to flamenco, and learned that piece. A few months later, my Mom took me to a concert of flamenco guitar, with male and female flamenco dancers. And, once again, my Grandfather took me to Town Hall: Feb. 1962, for the "Historic," SOLD OUT, Gala New York Performance, "The Incredible Carlos Montoya." I was 11. The concert was recorded and released in 1962, on RCA. I'm listening to it right now, the record, as I write this. At age 60, I immediately feel the same thrill that ran through my whole body and soul, at age 11, when Montoya plays his first notes. My little hands can be heard applauding, one amazing piece of Art after the other, on the recording: I was sitting right next to my Grandfather. I'm convinced that it was Carlos Montoya who awakened the Artist in me. |

|

My first real love affair, and my 3rd love affair with Beauty, came in the form of a very beautiful girl. I was 19, traveling through Scandinavia, when I met her: It was love at first sight, and we spent a month together, in the little town she lived in 45 min. north of Copenhagen. |

|

Just after I started painting, on one of my walks up the stream in my backyard, I met a neighbor who was very much involved in art. She knew much more about art than I did, and I started visiting her whenever I could. We would sit around her breakfast nook table and talk about art and artists. From Jan Peretz I first learned about Noguchi, David Smith, Turner, Arp, and so many of the great artists who were to influence my early direction in art. Jan was the first person who not only encouraged me as an artist, but gave me the distinct sense that an Artist was something one could actually be, in life. She lives in Boston now, where she is constantly learning about art and deeply involved in music, painting, and poetry. We lost touch during my 30 years in Santa Barbara, but reestablished contact 5 years ago, when I moved back to where I first started painting, and where I met her, Binghamton, NY. She was here about a month ago, and we spent 3 glorious days, looking through all the artwork I had done since she first encouraged me. As she was leaving, she said, “It’s amazing what you've become," which is the greatest compliment anyone has given me. |

|

When I first started painting, my main influence was Paul Klee. I went to Europe that summer and visited the Paul Klee Foundation in Bern, for a week. I spent every day at the Museum, looking at the over 300 Paul Klee paintings they then had on permanent exhibit. The highlight of the week was actually handling the pages, turning each page and looking for as long as I wanted at each drawing in one of the artist's sketchbooks, in the basement of the Museum. I think from that experience, I got a sense of what it was like to create art every day. |

|

My Dad had grown up with Sy Boardman, they were childhood friends: So when I showed such interest in painting, he took me up to Sy's studio. This was 1970, and Sy was in his Chelsea studio that I was to see him in often, over the years: The same 4th floor walk up he painted in until he died, in 2005. Sy was very nice to me, at our first meeting. He showed me how to stretch canvas, paint in the acrylic "staining" technique he was then using, what kind of Japanese brush was best for it, and he gave me some big jars of acrylic paint. I didn't realize it at the time, but through Sy, who I continued to visit, I was absorbing the whole New York School approach to art, and creating art. |

|

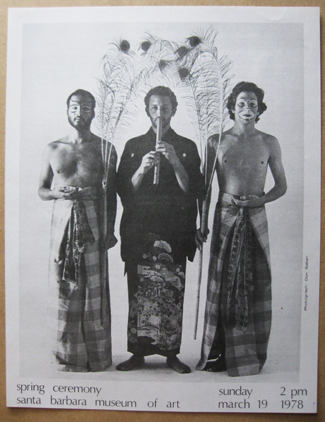

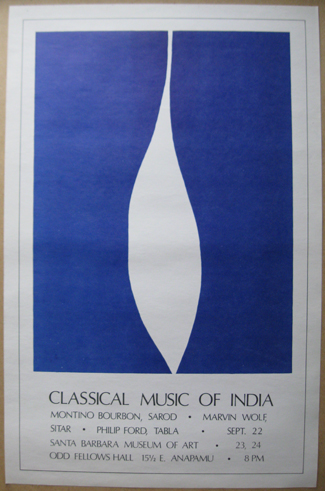

In 1974 I moved to Santa Barbara, and had a wonderful job as "Special Consultant" in the Curatorial Department of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. I worked directly under the Director of the museum, Paul Mills, who loved art. I did exhibits and catalogs, and in 1978 received a NEH grant as Project Director for my work at the Museum. I was painting all along, but by 1980 I started to feel that my painting wasn't developing properly, and I needed to do it full-time. I left the Museum, and have been creating art full-time ever since: More than half my life, now. Looking back on it, Mr. Mills had alot to do with my development as an artist. He sensed I was an artist first, and a curator only from my love of art: And I think he liked having an artist rattling around the Executive offices, in the midst of all the art historians. After all, it was an Art Museum. |

|

He definitely understood me better than I understood myself, at the time. I was 25 when I started working there. My first assignment was to redo a permanent exhibit he himself had designed. We discussed it in his office after I'd finished: His only criticism was I had changed the labels from small pins with tiny numbers, to large black circles with large numbers in white. He felt it was aesthetically inappropriate. I countered that I had many times seen older visitors squinting to read the numbers on the tiny pin heads, which were behind a glass case, and corresponded to a description of the pieces in the catalog. My labels stayed.

|

|

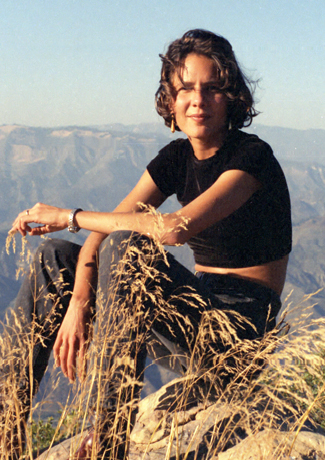

Looking back on it, the decision to create art full-time was clearly what led to my development as an artist. The first few years were extremely difficult. Doing the art was easy: Scraping up money to pay rent was always a challenge. But I was not alone. I had fallen in love with another beautiful girl, and this one turned out to be as true as she was beautiful. We fell in love back in 1977, when we were both working at the Art Museum. By the time I started doing art full-time, we were living together, and Annette really loved art. At the Rijksmuseum, we both decided that we liked Vermeer better than Rembrandt. Early one morning, we stood in front of "The Milkmaid" for half an hour, alone in the room. In Florence, we both liked Andrea del Sarto. Annette bought a Del Sarto catalog, in Italian, and after looking through it, showed me a beautiful little portrait, "Testa di Cristo." It was in SS. Annunziata so we headed over there to see it. We couldn't find it anywhere, so we asked a priest. "Yes," he said, "it's here. But first let me show you what else is here." He took us to a part of the Church not open to the public, filled with masterpieces. As we looked at these, he explained, "These great works of art were created here and have never left the Church." Then he took us back to the public part, where an older priest was performing a Service behind a small altar. There behind the lit candles, and the priest intoning Latin Scripture, was the small, beautiful portrait of Jesus. Andrea del Sarto had painted it for this Church about 470 years before we were looking at it: And they were still using it in daily Services! Annette and I went our separate ways in 1988, and we remain very close friends to this day. |

By the 3rd or 4th year of creating art full-time, study started to emerge, as what I now tell young artists the other half of being an artist is: "Art stands on two legs, practice and study." Study means studying the masters, and I've learned as much about being an artist from reading Beethoven's letters as Delacroix' Journal. Or listening to all of Beethoven's piano sonatas in the order they were created, to experience his development; or following Rembrandt's creative development, or Inness'. |

|

|

I fell in love with one of them, a Gifted poet. For 10 years we grew and developed as artists together. We have complementary Gifts: Hers is Truth, mine Beauty. We used to say that we illuminated each other's Gifts. And, we rubbed off on each other. I had been reading Greek literature in translation for years, convinced that I didn't have time to learn the ancient Greek: Christina dove right in. She got an unabridged Greek Lexicon, made a big chart for herself of the Greek alphabet, and learned Greek, totally on her own! One day she came out of her workroom all excited and said to me, "Mikey, Greek's really easy. It's just some of the letters that are different: But once you transliterate, you know right away what the word is." I took her word for it and decided to try. I was reading Aeschylus' "Prometheus Bound" at the time, in the Loeb edition, with the Greek on the left and a literal English translation on the right. Christina had showed me what the different Greek letters transliterated to. I got to the word, "ephemeral," in the English, and I was curious what the Greek for it might be. I looked over to the other side, found what I thought might be the Greek word, and transliterated. To my amazement, the Greek word was "ephemeroi." I was reading Greek! Sappho in English was one of my favorite poets, but reading Sappho in Greek, hearing the sound of her words, is one of the greatest love affairs with Beauty in my life. If you've ever tasted Louis XIII cognac, Sappho in Greek is like sipping 2,700 year old cognac. For years, Christina and I had wanted to get an OED: The 2 vol. "compact" edition with the magnifying glass. We'd see them at Antiquarian bookstores but never could afford one. Finally we managed to get one, used, and a few days later, Christina was reading one of Jefferson's letters and came to a word she didn't know. We both loved Jefferson's letters. She looked the word up in our American Heritage Dictionary but it wasn't in there, so she pulled out the OED and tried that. I was painting at the time, and we normally didn't interrupt each other, but this was special. Not only was the word in there, but as she read the chronological quotations of the history of the usage of that word, there, right before her eyes, under the magnifying glass, was the very sentence from the Jefferson letter she had been reading! She had to tell me, and we both felt something amazing had happened: It was the first time one of us had used our OED. |

Around this time, my best friend was a Classical violinist. Gilles had grown up in France and settled in Santa Barbara. We met at the first rehearsal for a concert we both performed in, in 1990: Our first conversation was about my favorite cellist, Pablo Casals. Gilles, me, and Christina would hang out together, at our place or his, talking passionately about art, listening to some old recording one of us had just discovered, developing as artists together. We went on trips together, visited museums together: In 1998 the three of us were in NYC, at the Noguchi, Frick, Morgan, and Met, studying art; in 2000 we were in Paris, at the Louvre every morning. Around 1994, Gilles and I had big breakthroughs in our careers, right around the same time. It had the same effect on both of us: We freaked out, for about a year! Both of us had always approached our art from a purely creative point of view: Suddenly we had, in my case Dealers, in his, Agents and Recording Companies telling us what to do! Fortunately, we had each other to work through it with. We finally realized that our art was really precious to us, and while we liked getting compensated for it, we weren't about to stop being artists, to turn out what business people were telling us would sell. We both stood up for ourselves, told our dealers that we had no intention of doing what they wanted; that we were the artists and they had it backwards: Either they could sell what we created or we'd find someone else who would. We've both continued in that direction and never looked back. Christina was there through all of this, and helped me and Gilles figure it out. |

|

|

The last thing Christina and I did together was turn a cafe in Santa Barbara into an Art School in disguise. We did that for 2 years, and attracted all the creatives in town. Now I was 50, she was 30, and we were talking about art all day and night, every day, with Gifted painters, musicians, poets, and dancers: Most of whom were the younger generation, 18-20. This was an incredible growth experience for everyone involved. Ten years later, most of those Gifted young artists are practicing professional fine artists. |

|

My other best friend at the time was also a musician. But his story is tragic. Freddy was a genius musician. He played clarinet through High School, and was one of 2-3 students out of 5-600 accepted in Cleveland Institute during George Szell. Freddy dropped out after a year. "I had learned all I could, and didn't want a career in Symphony Orchestra." I met him after a performance I gave, in Santa Barbara, in 1977. We started playing improvised music together. We performed together in the 1978 Summer Solstice Celebration, in SB. We lost touch with each other for years, until Christina and I ran into him in a record shop in town. I was just seriously getting into Bach, and asked Freddy some questions about Artist's interpretations of the Well-Tempered Clavier. About a year later, we ran into him at a Music Academy of the West concert. Our friend Andy was giving a recital, solo cello, and the Kaspers were there. After that, we started hanging out together, their house or ours. We'd talk about art, listen to music, and play music together. We went on trips together, to San Francisco, Pasadena, LA, and San Diego: Looking at art in all the Museums, and spending hours in music stores, where Freddy always came out with a huge stack of records and CDs. Freddy never worked. Their whole living room was the Music Room, wall to wall records, CDs, a clavichord Freddy had built, books on music, state of the art tube stereo, and two modern black leather listening chairs. Freddy spent, on average, 8 hours a day listening to music. I used to bring my Professional Musician friends over whenever they had a question about music I couldn't answer. Freddy knew more about music than anyone I've ever known. I once asked him, half in jest, what he was doing, and he gave me a very serious answer: "I'm trying to understand Music." One time, I was improvising with Bach's "Chaconne," when they came for dinner. Christina let them in, I kept playing, and when I stopped, Freddy, with a straight face, says, "You know, you're adding another voice to Bach." Another time, the four of us went to hear a violist we knew perform. She was in an all Women's String Quartet, and they were playing a piece by Fanny Mendelssohn. After the piece, I asked Freddy what he thought. "Well," he said, "If her brother had written music like that, we never would have heard of either of them." Around 1998, Freddy decided that Baroque flute was his calling. He started practicing every day for hours, to get his embrochure. After a year of practice, he'd play for us: It was beautiful. About 6 months after that, he got together with a harpsichordist who had the same approach to music, and they started to work on a repertoire, for a concert tour. They spent a year preparing for it. "Duo Galant" was the name they chose; they made a PR recording, set up tour dates, and were all set to go. About a year prior to that, Freddy had asked me to take him to the Doctor's, his wife didn't drive. He'd had a blister on his heel that wasn't going away, and the doctor wanted to remove it. The biopsy showed it was melanoma. They removed lymph nodes in his legs, it hadn't spread, Freddy changed his diet and got tested monthly: Everything was fine. Then he started feeling bad, and went in for a test: The melanoma had spread throughout his body, was in his brain, and the doctors gave him only a few months to live. I remember I was in the shower, when the call came, from Freddy's wife: Christina came in and told me. As I dried off, I thought to myself, "One has to make sure every day that one is doing exactly what one wants." Freddy died without getting to perform even the first of his concert dates. During his practice phase, on Baroque flute, he and his wife bought my 2nd oil painting. I made a cherry wood frame for it, and Freddy put it up in the music room, above his music stand, where he practiced. After he died, his wife gave it back to me. She said she couldn't look at it anymore because it reminded her too much of Freddy. |

|

Late in 2001 I had the biggest breakthrough in my painting career: My work was finally accepted in Japonesque Gallery, in San Francisco. Annette and I had discovered Japonesque in 1986, on a visit to San Francisco. Christina and I stopped there in 1993, on a 2 month road trip to Seattle; and for the first time, I showed the owner, Koichi Hara, my art. This resulted in a 2 hour conversation about art, and Mr. Hara telling me my art wasn't good enough for his Gallery. Japonesque is the most beautiful Art Gallery I have ever seen: Not only is everything in it beautiful, but Koichi walks around arranging everything perfectly, all day. Every few years, I'd stop in and show Koichi my latest work: "Not good enough." I stopped in again in 2001, with slides a friend of mine had taken of my latest paintings. Koichi held them up to the light, looked for a long time, turned to me and said, "What happened?" He said he'd have to see the actual paintings, so he picked out 5 or 6 from the slides, I drove home and brought the paintings up. |

|

|

|

Throughout my years in Santa Barbara, I always had in the back of my mind that something special had happened in Binghamton, in 1970, when I was 20 and started painting; and that I should go back there and find out what it was. I finally did that, early in 2006. Right away, it had a great effect on my painting. What I found was that the nature here is incredibly stimulating, visually. After a long winter of bare trees and white snow, Spring arrives, and every time you go out, you see the most beautiful forms and colors, and it's different every day. It's no coincidence that I started painting here, in Spring. Also, the natural lighting changes moment to moment, and this too is visually stimulating. I'm looking out my window now and the sky is blue-grey, overcast. It's early morning, Halloween, and the lighting outside sets off the bright yellow and orange of Fall leaves. Behind that is the long curve of a hill, in the distance. It is the curve of Beauty. |

|

|

|

POSTSCRIPT I have to say here that none of this happened in a vacuum. I had unconditional love and support, until they died, from both parents; my Mom’s parents; my Dad’s Mother; and my Mom’s brother, who is still alive at 93. My paternal grandfather I never knew: He had died before I was born.

|

|

I'm really not sure what I learned from my Mom's brother, Uncle Buddy. He certainly was a big part of my life, growing up. Until I moved to Santa Barbara, at age 24, going over to Buddy and Marion's was a regular part of my life, and had been since childhood. Buddy was always in his shop, making something. And I'd go there when I needed help, making something. Back when I was 10, and the adults were cultivating my Gift, Buddy's contribution was to design and help me make a beautiful shelf, to display my rock collection: It hung on the wall in my bedroom, and that's where I'd be looking into pockets of crystals with the magnifying glass. He'd show me how to do whatever I didn't know how to do, then he'd go back to work on what he was making; and I'd finish what I was making. I just thought of this now, but I guess I learned at an early age, how two people can be in the same place, each working on their own thing, without disturbing each other: Something which characterized my relationships with Annette and Christina, and Gilles and I used to do. But Buddy and I always had long conversations about things, also. Buddy and Marion loved art, and like me, travelled all over Europe mainly to spend time in the Museums. I once called up to arrange a time for me to visit them: It was right after my Mom had died, and I was in the city, visiting old friends and family who hadn't been able to make it to Florida for the memorial. Marion answered, and we ended up having a half hour conversation about the paintings in the Frick, which both of us had just visited: During that conversation, we both realized that the Frick was our favorite Museum in New York City. That's always what it was like around the dinner table, at their house. Buddy recommended books for me to read, too: Ben Franklin's "Autobiography" and Leonardo's "Notebooks" came into my life, through him: Two books I value to this day; constantly reread; and have recommended to many young artists. Perhaps another thing I learned from Buddy was a habit of work. Buddy would come home from work, eat dinner, and go into his shop to work: Both of us work all the time, and it's always our own work we're working on. I think we always sensed that we were alot alike. And it wasn't just genetic, because my brother's nothing like us. Now that I think about it, I never saw Buddy watching tv: I haven't had a tv since I started painting, in 1970. Of all the important early influences in my life, Buddy and Marion are the only ones still alive: Still in the same house I visited them in so often. Buddy is still, at age 93, working in his shop all the time. |

|